Crown Heights, 1991: violence erupts between Orthodox Jews and African-Americans. Although the outbreak only lasts a few days, ripples of after-effects were felt for years. Playwright Anna Deveare Smith interviewed over a hundred people affected by the conflict, recorded their stories, and created Fires in the Mirror out of monologues made from their words.

Firehouse theatre’s production of the play, directed by Katrinah Carol Lewis and performed by Jamar Jones, brings the story of the Crown Heights riots to life and challenges the audience to view it from a variety of perspectives. By the end of the show, you may come away with more questions than you had to begin with.

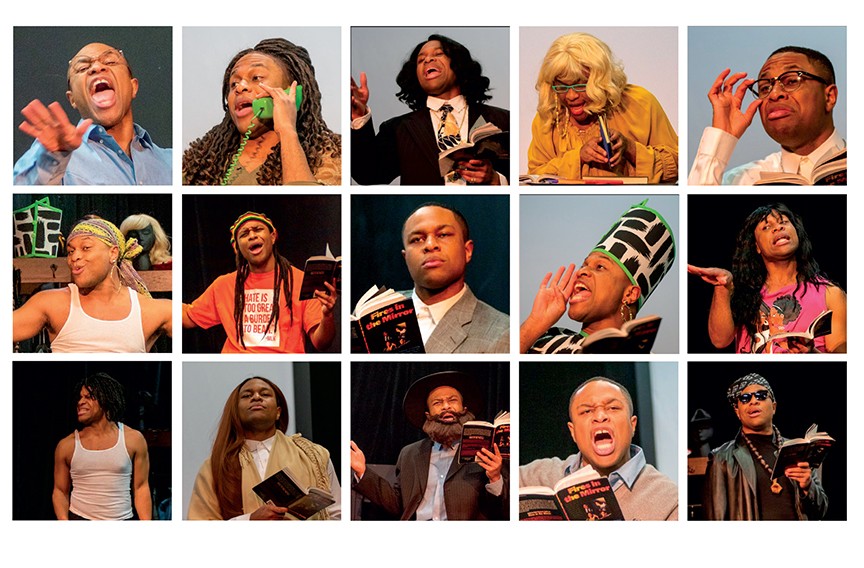

Jones effortlessly switched between 26 roles as he changed costumes onstage, ad-libbing noises in character as the clothes flew on and off. The show was costumed colorfully by Margarette Joyner, who managed to find the simplest ways for Jones to transform while the accompanying audio and images compiled by Lewis cleansed the audience’s palette. However, be warned: because of the many perspectives, the play lasts 150 minutes.

A few of the monologues in particular stand out, because Jones seems to so perfectly embody the people who first delivered them. It is as if they were speaking through him, such as prominent Reverend Al Sharpton and his foil, Rabbi Joseph Spielman. With the help of dialect expert Erica Hughes, Jones’ voice split into a prism of distinct voices.

The titular mirror was used in both the beginning and end of the play. Jones turned it towards the audience, slowly rotating it to make us consider more deeply the words we were hearing. Combined with the lights, the mirror was a thought-provoking prop, which Jones worked effortlessly, moving it to make the reflection flow fluidly across our masked faces.

Besides the mirror, the set was simple, consisting of a couple tables and props, with a projector in the backdrop to display the images and hangers on the side housing the cluttered rainbow of costumes and wigs, giving the audience a glimpse of what was to come. But most of the sense of space came from the perfectly timed lighting cues.(Production designed by Todd Labelle).

After the show, I had the privilege of staying for a backstage talk with Lewis and Jones. They explained that they had chosen this play because of its powerful impact that they believed (rightly) that Jamar could deliver to the audience. It isn’t the first time the two collaborated, but it is the biggest project Jones has ever taken on as a solo performer, though he says he’d do it again in a heartbeat.

Overall, the play will leave you feeling haunted. The final monologue, taken from Carmel Cato, the African immigrant who lost his young son to the accident that spurred the start of the riots; brought many of us to tears. That, in combination with all the voices and stories, tirelessly translated to the stage, make for a deeply moving production.